Did Thomas Jefferson Love Mac and Cheese?

Thomas Jefferson didn't just love mac and cheese - he helped revolutionize it in America. During his time as U.S. minister to France, he fell hard for European pasta and even brought enslaved chef James Hemings to Paris to expert French cooking techniques. He was so passionate about the dish that he imported a special macaroni press from Naples and documented precise recipes. The story behind America's favorite comfort food goes far deeper than you'd expect.

Jefferson's Culinary Journey to France

Thomas Jefferson's five-year stint as U.S. minister to France altered not just his palate but American culinary history. When you look at how Jefferson immersed himself in French cuisine during his time in Paris from 1784 to 1789, you'll find he wasn't alone in this gastronomic journey.

Jefferson brought James Hemings, an enslaved chef, to Paris where he trained in prestigious French kitchens. As any culinary historian will tell you, this decision had far-reaching effects on American food culture. Hemings perfected French techniques and ran Jefferson's Paris kitchen, later introducing dishes like macaroni and cheese to American tables.

Jefferson's enthusiasm for European foods didn't end when he returned home - he continued importing macaroni and other ingredients, helping to blend French sophistication with American tastes. His appreciation for cheese extended to varieties like fresh Mozzarella cheese, which was already well-established in Italian cuisine by the 18th century.

The Unsung Hero: James Hemings' Legacy

Behind Jefferson's culinary explorations stood an exceptional talent: James Hemings, who played a vital role in bringing macaroni and cheese to American tables. As Thomas Jefferson's enslaved chef, Hemings attained expertise in French cuisine during their five-year stay in Paris, where he trained at elite establishments and even served in the Prince of Conde's royal kitchen.

His mastery of fresh cheese making helped establish new standards for American dairy products. You might be surprised to learn that this "Culinary Founding Father" was the brother of Sally Hemings and one of only two enslaved people Jefferson ever freed.

Hemings' proficiency went beyond macaroni and cheese recipes; he revolutionized American cooking by blending French techniques with Virginia traditions. Before leaving his position, he trained his brother Peter to continue his culinary legacy, ensuring his refined cooking style would influence future generations of American cuisine.

From Monticello to America's Tables

After returning from France, Monticello became the epicenter of America's macaroni and cheese revolution, with Jefferson's 86 crates of French culinary equipment altering his Virginia estate into a fusion kitchen. You can trace the dish's American expedition through the skilled hands of James Hemings, who perfected French cuisine and created a unique blend of European and Virginian flavors.

The impact of Monticello's mac and cheese spread throughout America, particularly through:

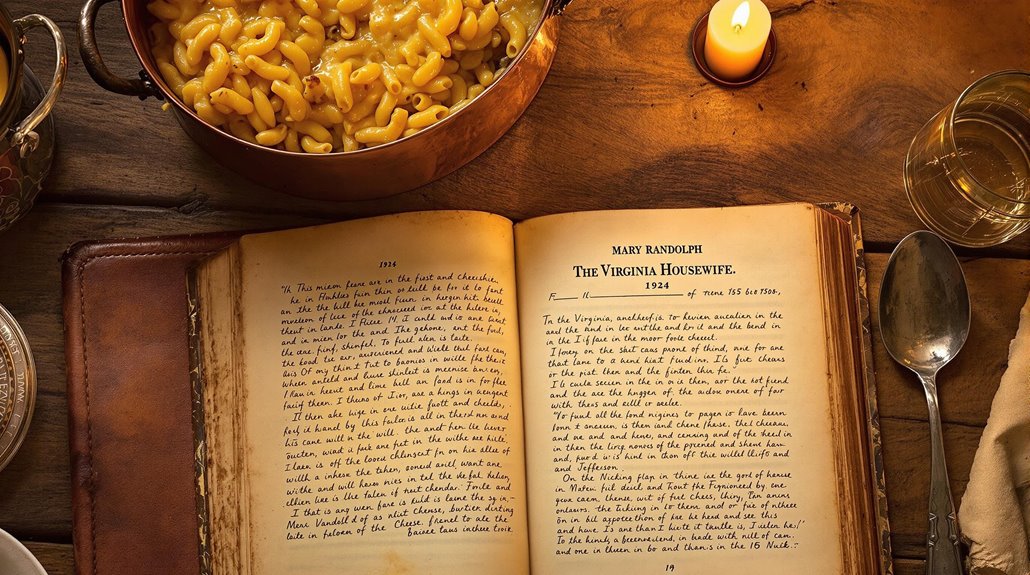

- Mary Randolph's groundbreaking publication in "The Virginia Housewife"

- Jefferson's detailed pasta recipe using semolina flour, eggs, and milk

- James Hemings' culinary mastery, which he passed down to his brother Peter

Today's beloved mac and cheese owes its American roots to this perfect storm of French influence, Jefferson's curiosity, and Hemings' culinary expertise at Monticello. Jefferson's appreciation for fine cheese likely stemmed from the French nobility's love of fromage de Parme, which had already been celebrated in Europe for centuries.

The Historic Macaroni Press and Recipe

Deep within Jefferson's culinary archives lies a fascinating piece of history: the macaroni press he acquired from Naples in 1789. William Short procured this special mold and sent it to Jefferson in Paris, who later brought it to Monticello. You can still find Jefferson's detailed drawings and descriptions of how the pasta machine operated in Italy.

What's even more intriguing is the surviving macaroni and cheese recipe in Jefferson's handwriting. Though he penned it himself, the recipe likely came from an enslaved chef at Monticello. The instructions reveal a simple yet precise method: combining eggs, milk, flour, and salt without water, then rolling the dough into thin strips. Jefferson's passion for pasta continued throughout his life, as he regularly imported it from Europe.

Mary Randolph's Published Recipe Legacy

The first published American macaroni and cheese recipe emerged in Mary Randolph's pioneering 1824 cookbook "The Virginia Housewife." While Jefferson had his personal recipe notes, Randolph's work gave the dish its formal debut in print, helping establish it as a true American staple.

You might wonder how Randolph's recipe came to be. Consider these fascinating connections:

- Her family ties to Thomas Jefferson through marriage and distant relations gave her access to his culinary advancements

- Though her Federalist husband opposed Jefferson politically, their shared love of fine food rose above politics

- The recipe likely drew from the skills of enslaved Black cooks, including Jefferson's renowned chef James Hemings

Randolph's published version of macaroni and cheese helped convert this dish from an elite novelty into a beloved American classic.

The True Origins of Mac and Cheese

While Thomas Jefferson may have popularized macaroni and cheese in America, this beloved dish's story begins far earlier in history. You'll find its origins dating back to ancient Rome in 160 BCE, long before America's third President encountered it. The combination of pasta and cheese first appeared in Italian cookbooks during the 13th century, including notable works like Liber de coquina and Libro della cocina.